Truth gains more even by the errors of one who, with due study and preparation, thinks for himself, than by the true opinions of those who only hold them because they do not suffer themselves to think.

John Stuart Mill

It’s been a while now since I last wrote about the Teaching Sequence for Independence, so I’ll start with a brief recap on what has come to be meant by ‘independent learning’. Up until relatively recently there has been a strongly held belief amongst many teachers that pupils will only become independent if we encourage our pupils to learn independently. In essence, this usually means independently of the teacher. This is, of course, nuts. If we really want our pupils to flourish, then we should give them free and unfettered access to our expertise.

Every year we see universities claiming that undergraduates are unable to learn independently and accusing schools for ‘spoon feeding’. Quite rightly, schools point out that they do loads of ‘independent learning’ and so it must be the fault of universities themselves because of all those tedious lectures. And never the twain shall meet. I reckon that we’ve made a mistake though. I think that doing ‘independent learning’ all too often results in dependency. If we really want our pupils to flourish then we need to teach them in such a way that will result in them actually becoming independent.

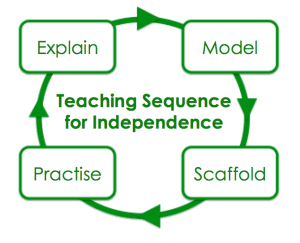

For the record, here is the teaching sequence I recommend following:

In a number of more recent posts about differentiation, I have made the case for making pupils struggle. But as a number of people have challenged me to explain my contention that if struggle is an important condition in which learning occurs, surely strategies like direct instruction and ‘worked examples’ which seek to reduce struggle have no place?

In a number of more recent posts about differentiation, I have made the case for making pupils struggle. But as a number of people have challenged me to explain my contention that if struggle is an important condition in which learning occurs, surely strategies like direct instruction and ‘worked examples’ which seek to reduce struggle have no place?

I tried to address the question here, but In order to try to make my position clear, I offer the following theoretical underpinning:

Firstly, learning is a marathon not a sprint. As Kirschner, Sweller & Clark point out, “If nothing has changed in long-term memory, nothing has been learned.” This suggests we should be less concerned about what’s going on in individual lessons and more focussed on longer-term learning goals: what will pupils know or be able to do next lesson, next month or next year?

So how can we ensure that pupils make these long-term changes to memory? Robert Coe contends that “Learning happens when people have to think hard.” This seems right and is directly connected to Daniel Willingham‘s proposition that “Memory is the residue of thought.” What we think about is what we will remember and thinking ‘hard’ is more likely to produce long-term retention.

So far so good. But the problem is, as Daniel Kahneman points out in Thinking, Fast and Slow, “Anything that occupies your working memory reduces your ability to think.” He discusses that fact that maintaining a walking speed above 14 minutes a mile will occupy working memory and therefore reduce our ability to think. If someone asks us to think about a complex problem when we are walking we will, most probably, stop in order to give the matter our full attention. This presents us with something of a vicious circle: until we have ‘thought hard’ about a subject we will be unlikely to have transferred essential knowledge from our working memory to long-term memory, but unless we think hard, such transfer is unlikely.

The problem was neatly expressed by Ralph Waldo Emerson when he said, “Every artist was first an amateur.” Willingham puts it another way:

Whenever you see an expert doing something differently from the way a non-expert does it, it may well be that the expert used to do it the way the novice does it, and that doing so was a necessary step on the way to expertise.

Experts and novices think in qualitatively different ways. But in order to be an expert, first we have to be a novice. The problem with ‘independent learning’ is that it attempts to short cut this process and assumes that if we get novices to work on the sorts of problems experts work on then they will think like experts. Sadly, this is not the case.

This then is the reason why I think direction instruction and worked examples may be vital. Explaining new concepts clearly provides pupils with the knowledge they need in order to think. You cannot think about something you know nothing about. And the more you know, the more sophisticated your thinking is likely to be. I am able to think deeply about education, but am incapable of thinking about quantum physics because I know nothing about it.

Then, if I want pupils to produce anything of worth, I need to give them access to my expert thought processes. I need to ‘show’ them how I think by talking through an example. If I don’t do this and instead rely on bullet pointed success criteria, then pupils will only have a very vague idea of how to improve. It turns out we don’t learn well from watch experts perform. I used to believe that I could become better at tennis by watching Wimbledon. Frustratingly, it wasn’t until I took some lessons and had an expert coach explain how to stand, how to hold the racket, how to move and, crucially, how to think, that I started to improve.

So, the Explain and Model stages of the teaching sequence are about providing the material we want our pupils to think about and reducing the quantity of information they are required to hold in working memory by providing them with the knowledge they haven’t yet gotten around to storing in long-term memory. This allows them to concentrate on thinking rather than on remembering. The Scaffold stage is where pupils can be asked to think in increasingly challenging circumstances: the scaffolding we provide should allow pupils to think about things which seem impossible; it should seek to make the impossible possible. And then pupils are ready to Practise by tackling problems of increasing complexity in an effort to move them from competence to mastery. If we’re content with mere competence, we’re unlikely to get to the point where our understanding of complex concepts can be drawn into working memory as complete chunks whenever needed. The changes that will have taken place in long-term memory must be practised in order for pupils to be truly independent.

The first two stages are about freeing up working memory to allow students to think and therefore remember and the final two stages are to provide support and opportunity to ensure that thinking becomes increasing less dependent on the teacher.

I hope this clarification is helpful. If you’re interested, the following series of posts might help to explain in further detail:

Independence vs independent learning

Great teaching happens in cycles

Stage 1: Explain

Stage 2: Model

Stage 3: Scaffold

Stage 4: Practise

[…] Full text […]

Earlier today I went through the 2012 ‘Higher’ Maths paper with an very bright 11 year-old boy. I have ‘expertise’ on the subject but it very quickly proved to be totally unnecessary because he could work through the paper by himself, in some cases with astonishing ease. So it is definitely not ‘nuts’ to expect some children to work independently.

It follows that actual learning cannot take place unless children are struggling. After all, if we can do something what would be the point of ‘learning’ it except for exam practice.

Clearly the student you were working with already had the necessary expertise to be independent. Working or learning independently should be an end not a means. It is nuts to expect that independence is achieved through minimal guidance.

I’ve made that exact point about struggle in the posts I link to in the first few paragraphs of the post – this was an attempt to explain the need for teacher led instruction as part of the conditions required for struggle.

I disagree. I regularly give minimal (sometimes very) and let the pupil do it by herself. With certain children this is indeed what you should do because they sometimes don’t need your expertise for a given piece of work (less often you will also find the children understand the concept better than the teacher just based on the initial input). This happens a lot in maths because bright children can sometimes see where a certain idea is supposed to go. You will find this is extremely common.

Well, far be it for to criticise your practice. I’m sure whatever you do is excellent. But this does beg a few questions: How do you think children understand concepts without having them explained? Some sort of osmosis?

Do you remember the kid at school who could work out the square roots of numbers with ridiculously long decimal places? Perhaps. I do. There were a couple I can think of. Henry was one. He could work out anything, it seemed. We used to test him with a calculator.

Do you remember the kid at school who instinctively understood and was able to explain the concepts of mediaeval peasantry and feudalism, and how the power base of serfdom was affected by first the Black Death and then the Statute of Labourers in the fourteenth century? No.

Maybe maths is different? Is there something about numbers that allows some of us to process complex mathematical concepts relatively straightforwardly? Maybe. I’m not a mathematician.

My first example is anecdotal because it IS the sort of thing you might hear about. I wouldn’t normally use an anecdote as evidence, but then muzzyizzit’s example is anecdotal, too.

What I would say, however, is that whilst I’m sure what muzzyizzit says is true, there is an explanation somewhere. I don’t know if there are any studies about mathematical concepts. In any case, that student was either gifted or had the expertise.

(boy or herself?) There are lots of concepts on the Higher syllabus that I simply could not imagine any pupil of any age working out for themselves (Trigonometry? Surds?)and I’ve been a Maths teacher for 17 years.

Picking it up quickly, maybe, working it out from first principles as they went along, no.

Of course there is a big area , language, that is almost never explained.and it is like breathing to humans.

What you have in mind, of course, is stuff that requires some input from the environment. Clearly some input is needed to to get the ball rolling, so to speak, but most of it can happen without us teachers getting involved much in it. If this doesn’t happen education is basically impossible.

I think we fundamentally disagree on this. I appear to believe the exact opposite to you 🙂

just thinking aloud here, so to speak. I wonder whether this might depend on the type of concept. I mean, nobody taught the first person to identify the concept, did they? Maybe some concepts just ‘click’ in you head. But there again, when you give a pupil a maths question to solve independently, do they necessarily need to use a new concept? Perhaps the solution just (just!) requires the pupil to see that it will require the application of a selection of mathematical processes they have already studied (meta cognition?). So many questions and shades of meaning/ understanding. one reason why we are in a fascinating profession.

I’ll be honest – this doesn’t have the ring of truth to me.

There is so much of mathematics that requires an understanding of notation that it is not possible to just ‘have a feel for it’. Probability, histograms, similarity, differentiation, vectors, surds, standard form – these are just a few that spring to mind.

There are also many areas where self-extending by applying an already known technique leads to bother – if you doubt that, give a pupil a quadratic equation and watch them first try to solve it in the same manner they’d solve a linear equation. It’d be an extraordinary leap for them to factorise it themself without being taught it. Reverse percentages are another classic case of this, with pupils thinking the opposite of an increase of 50% is a reduction of 50%

I can see no fault with the teaching sequence outlined above, but I’d add in regular, spaced testing to help with retention of skills, and non-directed problems to help with motivation and application.

Thanks for sharing this David!

You have to be taught a lot of it, of course. Histograms are a good example. However in such cases what the children can’t do by themselves is the conventions not the concepts. One you show the child what is expected, the actual learning can take independently. Indeed, that is what being very bright really is about.

The same boy I mentioned before can not only solve quadratic equations but he can derive the quadratic formula. He certainly understands that a 50% reduction is not the opposite of a 50% increase. He was taught the basics, obviously. The point is he does a lot of it independently and his understanding can be much better than his teachers at various levels and points.

Incidentally this is common if you work with grammar school kids.

I do teach them, and it’s certainly not common.

The pupil you are talking about is an exception, and you’re clearly indicating that this pupil has accelerated his learning. He didn’t become an independent learner through working independently from the teacher, but because he had some other motivation to do so (hopefully not by pushy parents)

The job of the teacher, at its most basic, is to teach. Well qualified and trained teachers are paid to teach. Supervising independent learning is not teaching. There may well be children who show astonishing skill with numbers, e.g. autistic savants. There are children who may indeed work out, with little to no help, key concepts. But surely explaining key concepts is a fundamental job for the teacher? Those who ‘get it’ immediately can be taken further, and may well do this independently, those who don’t can be helped. Teachers ignoring this basic job are being paid to do what exactly?

Yes – if we teach someone who does ‘just get it’ then we should teach them something they don’t ‘just get’. Maybe if children are not struggling to understand what we’re teaching, that miight indicate a failing on our part and not something of which we should feel proud.

‘Supervising independent learning’ while giving support along the way is what teaching is about. All learning is essentially independent. This is a tautology. The teacher’s input is minute compared to what the student ends up knowing. I find it very curious that there is a debate about this.

Do you really find it curious that there’s a debate about child centred vs teacher led instruction? I’m assuming that’s because you believe you’re right? Unsurprisingly, so does everyone else. This debate is pretty fundamental to education. Not having the debate is potentially professionally irresponsible. And at best it’s incurious.

[…] Truth gains more even by the errors of one who, with due study and preparation, thinks for himself, than by the true opinions of those who only hold them because they do not suffer themselves to think. […]

don’t bash pushy parents.:)

It is a truism that what you know is almost entirely a result of new connections and links you made from a degenerate data. What teachers taught you is a tiny part of it. Obviously.

Truisms are not, generally, true. The links and connections you can make are entirely dependent on what you know. The tiny part teachers teach should be made up of stuff children are unlikely to encounter outside of school.

I agree with that last statement wholeheartedly.

By the way, I just bought your book and I am 14% into it on my Kindle. I love it a lot so far.

Thank you. In the book I’ve expanded on my ideas about independence – maybe they’ll make a bit more sense 🙂

I agree. The best explanations do not hand it all on a plate (even in uni lectures) but model how the relevant questions should come to be formulated and how to go about answering them. Thinking as a science teacher, such disciplines can be filtered down from expert and professional level practice. I learned ‘back of the envelope calculations’ late in education, as-modelled by my PhD supervisor, but I can train younger students to set up and solve such problems, now that I recognise how powerful and useful the approach is. (I have to credit my dad (engineer) at the dinner table here, too, for modelling mathematical derivations in a way my school science teachers never did). The OCR B A Level Physics course (IoP – designed) is an excellent example of an approach from first principles, gently guided and accessible. But, as I saw again today with Y12 Chemistry and as I once fluffed my way through in my own uni interview, you have to be told whether phenol is an acid or a base, because it can be argued either way from chemical principles (well, you could test it, but it’s too toxic for them so even that’s a demo). Without information, nothing can be modelled, linked, shaped or predicted.

Yep. Basically I want explanations to be as simple as possible, but no simpler. We should embrace the fact that some things are hard to understand and work harder to explain them as simply as we can.

Great post David. I feel a long overdue sea-change when I read how passionately you believe in the voice and expertise of the teacher. One thing a class won’t experience if provided with a mere ‘facilitation’ approach, is an educator’s love of their subject. What better role model for kids than an articulate adult who is passionate about their subject?

True enough – I wasn’t even factoring that in, but yes: enthusiasm – en theos – full of the god 🙂

It applies to teachers too. If you make them spend too much of their time obsessing about whether they are ticking all of the necessary boxes and the other backside-covering we have to deal with, it leaves less space for simply teaching well.

Rings a bell. I have a lifelong interest in the science of aeronautics (‘hobby’ I suppose, though I don’t make models or anything and I don’t like the word). This stuff was certainly never covered in any school I went to. It’s had nothing to do with my work. So I’ve been an ‘independent learner’. Mostly I’ve learned from books and, lately, internet. But currently I’m stuck with a particularly difficult concept that I simply cannot get my head around — read a bit, think a lot, read again, still elusive. But I know a professional aerodynamicist with communication skills would sort me out in no time.

[…] Truth gains more even by the errors of one who, with due study and preparation, thinks for himself, than by the true opinions of those who only hold them because they do not suffer themselves to think. John Stuart Mill It’s been a while now since I last wrote about the Teaching Sequence for Independence, […]

[…] Teaching for independence: from competence to mastery […]

[…] https://www.learningspy.co.uk/learning/teaching-independence-learning-difficult/ […]

[…] Teaching for independence: thinking, memory & mastery Independence vs independent learning Great teaching happens in cycles Stage 1: Explain Stage 2: Model Stage 3: Scaffold Stage 4: Practise […]

[…] led me to conceive of teaching as a sequence. I’ve written extensively about the Teaching Sequence for Independence which can, I think, be adapted to allow students to master most anything, but it wasn’t until […]