It is commonly and widely accepted that feedback is the best, brightest and shiniest thing we can be doing as teachers, and the more of it the better. Ever since Prof Hattie published Visible Learning in 2009 we have had conclusive proof: according to Hattie’s meta-analyses, feedback has the highest effect size of any teacher invention. QED. And this has led, unsurprisingly, to an avalanche of blogs (many of which I’ve been responsible for) on how to give feedback more efficiently, frequently and effectively. Teachers the world over have rejoiced.

But perhaps we’ve been a little uncritical on just how best we should be thinking about feedback? I reported recently that there are some causes for concern and caution when it comes to trusting the ‘effect sizes’ produced by meta-analyses, and, as yet, No one’s come up with a defence that makes much in the way of sense. But forget such mathematical minutiae for just a moment. Take a look at the abstract for Hattie’s 2007 paper The Power of Feedback:

Feedback is one of the most powerful influences on learning and achievement, but this impact can be either positive or negative. Its power is frequently mentioned in articles about learning and teaching, but surprisingly few recent studies have systematically investigated its meaning. This article provides a conceptual analysis of feedback and reviews the evidence related to its impact on learning and achievement. This evidence shows that although feedback is among the major influences, the type of feedback and the way it is given can be differentially effective. A model of feedback is then proposed that identifies the particular properties and circumstances that make it effective, and some typically thorny issues are discussed, including the timing of feedback and the effects of positive and negative feedback. Finally, this analysis is used to suggest ways in which feedback can be used to enhance its effectiveness in classrooms. [My emphasis]

That’s rather startling, isn’t it? Although feedback is hugely powerful, it’s “impact can be either positive or negative.” Maybe just giving feedback willy-nilly is something to be avoided; perhaps we need to be a bit more mindful about what we’re doing? AfL guru, Dylan Wiliam also reminds us that giving feedback can often backfire and have startlingly unintended consequences: This table illustrated just how easy it is to get it wrong. How often might our feedback result in pupils making less effort, aiming lower and abandoning goals? Too often. Clearly, there are cases where no feedback at all might be preferable.So, baldly stating that giving feedback is always desirable misses much of the nuance in Hattie’s research. Consider this:

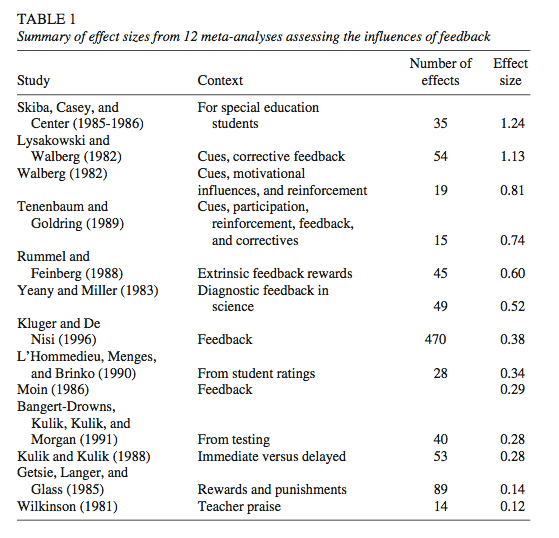

This table illustrated just how easy it is to get it wrong. How often might our feedback result in pupils making less effort, aiming lower and abandoning goals? Too often. Clearly, there are cases where no feedback at all might be preferable.So, baldly stating that giving feedback is always desirable misses much of the nuance in Hattie’s research. Consider this: Seven of the studies on feedback analysed by Hattie actually have effect sizes below his ‘hinge point’ of 0.4, although the average effect size is 0.79 (It’s worth reading one of my previous blog posts for explanation and critique of effect sizes.)So, as Hattie himself acknowledges, some forms of feedback are more effective than others. He offers us this list of ‘feedback effects’:

Seven of the studies on feedback analysed by Hattie actually have effect sizes below his ‘hinge point’ of 0.4, although the average effect size is 0.79 (It’s worth reading one of my previous blog posts for explanation and critique of effect sizes.)So, as Hattie himself acknowledges, some forms of feedback are more effective than others. He offers us this list of ‘feedback effects’: Right at the top is ‘cues’. Now, it comes as absolutely no surprise to me that using cues will boost pupils’ performance. How could it not? But as I’ve already explored at length, increasing performance is not the best route to improve learning. At number 2 is the unhelpfully labelled ‘feedback’. How is ‘feedback’ a feedback effect? All Hattie tells us is, “Those studies showing the highest effect sizes involved students receiving information feedback about a task and how to do it more effectively.” Clear?Worryingly, when we start interrogating the body of the text, Hattie finds the following:

Right at the top is ‘cues’. Now, it comes as absolutely no surprise to me that using cues will boost pupils’ performance. How could it not? But as I’ve already explored at length, increasing performance is not the best route to improve learning. At number 2 is the unhelpfully labelled ‘feedback’. How is ‘feedback’ a feedback effect? All Hattie tells us is, “Those studies showing the highest effect sizes involved students receiving information feedback about a task and how to do it more effectively.” Clear?Worryingly, when we start interrogating the body of the text, Hattie finds the following:

[F]eedback is more effective when it provides information on correct rather than incorrect responses and when it builds on changes from previous trails. The impact of feedback was also influenced by the difficulty of goals and tasks. It appears to have the most impact when goals are specific and challenging but task complexity is low. Praise for task performance appears to be ineffective, which is hardly surprising because it contains such little learning-related information. It appears to be more effective when there are perceived low rather than high levels of threat to self-esteem, presumably because low-threat conditions allow attention to be paid to the feedback.

Let’s just sum that up. In order to be considered effective, feedback should:

- only provide information on correct responses

- only be given on simple tasks

- avoid praising performance

- make you feel good

So as long as kids do simple tasks and get all the answers right, feedback will be effective? What’s the point in that?Fortunately, Hattie proposes a somewhat more sophisticated model for effective homework:

Simply providing more feedback is not the answer, because it is necessary to consider the nature of the feedback, the timing, and how the student ‘receives’ this feedback (or, better, actively seeks the feedback). (p 101)

Quite right. We need to be a lot more critical of being told that anything is ‘the answer’. And moreover

With inefficient learners, it is better for a teacher to provide elaborations through instruction than to provide feedback on poorly understood concepts… Feedback can only build on something; it is of little use when there is no initial learning or surface information. (p 104)

So that’s clear. Whatever we do, we need to make our instruction, our teaching, as effective as possible before we attempt anything else. This is undoubtedly true and I’ve given a lot of thought on how we might design sequences of effective teaching. And guess what? There’s no one answer.

Now at the risk of disappearing down the rabbit hole of research, it’s also worth reading Bjork’s ideas about all this:

One common assumption has been that providing feedback from an external source (i.e., augmented feedback) during an acquisition phase fosters long-term learning to the extent that feedback is given immediately, accurately, and frequently. However, a number of studies in the motor and verbal domains have challenged this assumption. Empirical evidence suggests that delaying, reducing, and summarizing feedback can be better for long-term learning than providing immediate, trial-by-trial feedback. However, the very feedback schedules that facilitate learning can have negligible (or even detrimental) performance effects during the acquisition phase… Numerous studies—some of them dating back decades—have shown that frequent and immediate feedback can, contrary to intuition, degrade learning. (p 23)

Why is this? Well apparently, “feedback that is given too immediately and too frequently can lead learners to overly depend on it as an aid during practice, a reliance that is no longer afforded during later assessments of long-term learning when feedback is removed”. Or to put it another way, giving pupils feedback turns them into crazed feedback junkies causing them to fall to pieces when they’re in a situation (an exam) where they can’t get their fix. If this is true and feedback is ‘merely’ a crutch to prop up performance during the ‘acquisition phase’ of learning, then we could be in real trouble. This absolutely doesn’t mean that we shouldn’t ever give pupils feedback on how they’re doing. But it does suggest that judiciously withholding, delaying and reducing feedback can boost long term retention and lead to sustained learning.How might we build this thinking into marking and feedback policies? Andy Day covers similar ground in his thoughtful post What if Feedback wasn’t all it was cracked up to be? and asks the million dollar question about opportunity cost: if teachers are expected to spend ever-increasing hours on marking and giving feedback, what effect will this have on their ability to teach effectively? He makes these 5 very pertinent points:

- Feedback can have a negative impact for students who have acquired insufficient knowledge or lack confidence in their ability to achieve goals. Time would be better spent on ensuring they have the requisite knowledge and/or trying to establish viable goals to which they can commit, rather than giving them feedback. Who, in my classes, does this apply to?

- Feedback is dismissed by students who don’t commit to the goal. There is no ‘gap’ to be closed. Or they self-select an alternative goal that may not involve learning. I’m increasingly of the opinion that many students who are routinely assigned ‘aspirational’ targets based on FFTD or 4 levels of progress – simply dismiss these. But school accountability systems designed to show inspectors the rigour of the progress data rarely acknowledge a capacity to change them to something more credible in the students’ eyes and re-engage their sense of a purpose.

- Feedback can have a deleterious impact if it is too positive in some circumstances. Committed students can interpret it as meaning my expectations of them are too low.

- Feedback can be too frequent. There are categories of feedback, and some of them have more impact if they are delayed.

- Feedback is the ‘silver bullet’ of the moment to determine quality of teacher performance. Previously it has been ‘sharing learning objectives’, ‘group discussion’, ‘multi-part lesson plans’. They didn’t crush the light out of teachers’ eyes. Feedback is the ‘must see’ totem now – but probably won’t be in four years’ time; something else will have replaced it as it didn’t do what it promised. Only, by then, we will have seen some valued colleagues pack their bags – not with marking – and depart for good.

Related posts

Feedback: it’s better to receive than to give

Is praise counter productive?

Deliberately difficult – why it’s better to make learning harder

In table 2 what is the difference between ‘feedback’ and the other types of feedback below, other than how it was done? I.e how does video feedback differ to feedback other than being on video?

Are the other feedback studies included in the 4157 studies?

I know, right? That’s the point I was trying to make – the lack of clarity is unhelpful

[…] It is commonly and widely accepted that feedback is the best thing we can be doing as teachers and the more of it the better. […]

Thank you for this, The suggestions on a way forward are much more helpful than a blanket criticism although I do see that your last post generated some interest which was also very valuable. Thank you also for drawing attention to Neil Gilbride’s http://www.youtube.com/channel/UCgYsvs3rNmKy4-ec1ajKyUQ/videos which also gives a way forward.

[…] Read more on The Learning Spy… […]

[…] Read more on The Learning Spy… […]

Where does this leave your ideas on DIRT and the dictum that ‘marking is planning’? Surely, that kind of genuinely differentiated feedback encourages a growth mindset and is manifestly positive.

It leaves me, as ever, questioning and reflecting on my practice.

I’m not about to abandon these ideas but it’s always good to delve deeper.

[…] It is commonly and widely accepted that feedback is the best, brightest and shiniest thing we can be doing as teachers, and the more of it the better. […]

Just about to read Hattie and Yates’s chapter on feedback with our reading group on Wed so your thoughts and Day’s points [I had forgotten these] are really helpful and timely-thank you. Robert Powell’s little book on Feedback and Marking is helpful and develops Hattie’s original data into teacher friendly useage and we all agreed here that we like Zoe Elder’s words of wisdom on feedback and most everything else! I’m not sure that feedback will go away like SOLO or PLTS as Day suggests-it’s a much bigger topic across many disciplines from a half time team talks to the plethora of talent shows on TV-feedback matters and makes a difference-if it is based on meaningful dresearch and the converations stimulated on blogs like this.

“I’m not sure that feedback will go away like SOLO or PLTS” – quite so: feedback is a routine part of communication. Teaching without giving feedback seems inconceivable. But it’s worth being aware that it isn’t magic fairy dust to sprinkle liberally over all we do.

[…] https://www.learningspy.co.uk/featured/reducing-feedback-might-increase-learning/ […]

[…] Force fed feedback: is less more? – David Didau on some of the perils of feedback […]

I have thoroughly enjoyed reading this and Andy’s blog on feedback. If nothing else it does make you reflect and think is what I’m doing right and is it the best for my pupils? And again the answer is I don’t know, probably, hopefully.

I do have one concern and that is about delayed feedback. I am unsure as to how closely related the bjork experiment is to how pupils learn in school. Am I right in thinking the verbal experiment is about acquisition of groups of words? I do worry that the suggestion that feedback should (could) be delayed is a good thing. I have always seen pupils receiving late feedback on work pay it no heed. The work has come and gone and the motivation to read and act on any feedback has passed too. This is subtly, but crucially different to the bjork experiment. Even when we mark books and give them back the next lesson that still represents a delay. There will have been other lessons and lots of cognitive “interference” since the lesson when the learning would have taken place.

I have started a RAG123 experiment for my year 11 class in which every book is marked every day. It gives me the opportunity to pick up misconceptions at source. It seems daft to see a pupil has a misconception about respiration and then consciously delay feedback. Perhaps it may be true that if I did delay the feedback it would lead to greater long term retention about respiration. However I would be risking the subsequent learning and knowledge acquisition foundering because of this misconception.

As ever your blogs are hugely readable and thought provoking. I suppose that this blog and that of Andy’s shows that learning is hugely complex and the act of giving effective feedback is hugely complex too.

Damian (@Benneypenyrheol)

Thanks Damian

You’re right: the point of all this is to embrace the uncertainty. It’s hard to be mindful of the fact that we don’t know what we don’t know.

One point though, I’m not referring to a single experiment – Bjork’s paper refers to a range of research which supports these findings in both the motor and verbal domains. Verbal here doesn’t mean remembering a few words but refers to the verbal domain as opposed to the motor domain. Basically, the motor domain is all about physical stuff whereas the verbal domain is connected to more purely mental activities. Does this make sense?

Thanks for responding David. I will have to read more on the bjork paper but thanks for showing the task wasn’t as simplistic as I suggested.

Embrace the uncertainty. I like that. I feel we need to continue to reflect on what we do and constantly question the impact of what we are doing.

Damian

I think perhaps the unintended consequence to this continual feedback without delay is that students won’t develop independence of thinking. Being uncertain of something and going to find the answer in a variety of sources could allow Ss to look at their own role in developing understanding. I think this approach fosters dependency on the teacher and is time/resources of the teacher better spent on having more energy to approach misconceptions at the next meeting. I can envision some anxious learners never wanted to think outside the box/ie only want the teacher to declare something factual/correct/right wrong and not develop mental mind wondering to independently learn.

Circling back over information and correcting for misconceptions can be pretty powerful.

[…] This post from @learningspy […]

Your blog has given me so much to think about–thanks. I am working with fourth graders (9 and 10 year olds) on writing paragraphs to compare two pieces of poetry. Based on some of your previous feedback posts and the links you provided, I experimented with just writing comments–no grades–on their latest paragraph, and then giving those back to students to read as they started on their next comparison task. It was interesting to see how they handled the comments and what kinds of questions they asked as they started writing. And I very much saw your point #1 in action. The really capable readers took off with the next task, comparing two new poems, and came up with interesting comparisons and connections that showed much deeper thinking than before. The struggling readers seemed to have more trouble with the second task and wanted clarification after every sentence: Is this right? What should I put next? In this case, perhaps I should have waited a bit before giving these students feedback. So much to think about but that’s what makes teaching so exciting!

[…] Force fed feedback: is less more? […]

[…] David Didau’s blog @learningspy outlines some of the potential negative impacts here […]

[…] back before deciding that it’s a good idea. Two powerful, recent posts, from Andy Day and David Didau, have laid out a number of criticisms to the current cult of feedback. Their points are numerous, […]

[…] The other way that spacing is set up is through the switching between the two topics in each unit of work. Deciding when to switch is contextual – a natural break in one topic is the switching point. For example, a few days on converting betweeen fractions and decimals before switching to working on calculating unknown angles would provide a few potentially fruitful opportunities. It gives the teacher a bit of time to assign any extra practice (perhaps for homework) to help some children to be ready for ordering fractions and decimals. It also gives the teacher a chance to delay feedback for a couple of days, which could be well worth experimenting with, as David Didau suggests here. […]

Hi David. I have a question. Can you expand a little more on immediate feedback? For instance, every week, I give my senior physics students a past exam question to complete. I take this up to mark. However, I then immediately give the students the worked solutions. In my mind, I do this so that they can see where they went well and where they went wrong whilst the experience of grappling with that problem is still fresh in the memory.

Another facet to this process that I should mention is that the question is always on a topic that we addressed 2-3 weeks previously in class. My thinking here is that this disrupts the decay of knowledge that naturally occurs subsequent to learning. Does this mean that the feedback is actually therefore delayed?

I find myself getting very confused around these notions of feedback. I can’t seem to disentangle feedback from teaching in general. For instance, if I give a test and find that students don’t understand X then this is feedback to me. If I then reteach X to those students then this is feedback to them. But isn’t this just… like… what you do? Does feedback have to be defined as prose at the end of a piece of ‘work’. If so, I’m going to struggle with translating all of the maths that I need to communicate into sections of prose. And how can I explain it if I’m not there? Confusing.

[…] we’re not usually told about feedback and the fact that it might be worth thinking about delaying or reducing the feedback we give. These musings have been important in developing my thinking, but I keep coming back to […]

[…] Feedback is always good […]

[…] using it a little more sparingly then we have been? For a more detailed discussion, have a read of this post. Wiliam says the following in his conclusions on […]

[…] There’s loads more more stuff on feedback in a blog post by David here. […]

[…] https://www.learningspy.co.uk/featured/reducing-feedback-might-increase-learning/ […]

[…] Force-fed feedback: is less more? Why AfL might be wrong Getting feedback right […]

[…] https://www.learningspy.co.uk/featured/reducing-feedback-might-increase-learning/ […]

[…] Feedback has a huge impact, but necessarily a positive one. […]

[…] Feedback has a huge impact, but necessarily a positive one. […]

[…] feedback shouldn’t be given so that students improve (see David’s excellent blog post ‘Force-fed feedback – Is less More?‘). Certainly, for feedback to be timely and purposeful, setting arbitrary weekly or […]

[…] Force fed feedback: is less more? 26th January 2014 […]

[…] evidence – that’s just wishful thinking. I’ve gone into this in much more detail here. That not to say there’s never a point to providing frequent and immediate feedback – […]

[…] Force fed feedback: is less more? […]

[…] been practising. (There are all sorts of flaws in this theory, many of which are described here.) But, if marking does not actually lead to children receiving feedback, maybe it’s a poor […]

[…] they’ve been practising. (There are all sorts of flaws in this theory, many of which I describe here.) But, if marking does not necessarily lead to children receiving feedback, maybe it’s a poor […]

[…] The problem with progress Part 1: learning vs performance Force fed feedback: is less more? […]

[…] https://www.learningspy.co.uk/featured/reducing-feedback-might-increase-learning/ […]